Robert Pirsig's classic exploration of the richness to be found in blending both "classical" and "romantic" is an exemplary philosophy to consider: taking both gestalt and rational applications in a hybrid approach to life. Magic is, for many players, serious business. Before you jump away because I invoked an internet meme and wildly popular card game in the same sentence, consider how much time, effort, and investment you've put into what most would call a hobby: tuning decks and taking them to tournaments is, to the outside world, the nerdy equivalent to tweaking and modifying an import car and taking it to a car show every weekend or so. Both hobbies require significant time, technical knowledge, and monetary investment to achieve notable success. Professionals can earn an often meager living off of success and selling cumulative knowledge, tips, and parts to others (StarCityGames, anyone?).

Of course, being a gearhead and Magic player are on different orders of expense. I've talked about playing without spending a lot of money and that idea isn't what I'm going to talk about today. The current philosophy of deck design can be derived from Sligh, or rather its designer Jay Schneider and his then-revolutionary vision. Where is the future of Magic deck design heading? What can we do now, today to push the limits of deck building? Before we get there, let's look at the historical development of deck design.

In the beginning, there was darkness.

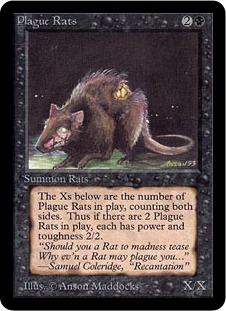

Still misses the limelight.

The four-of rule resulted from the need to generate consistent fairness in emerging organized play. Fledgling tournaments meant little when those who had multiples of the broken cards played (they almost always won). The four-of rule was the first revolution on deck design: you now needed more then a handful of different cards to create a deck. Of course, even with this "heavy restriction" the broken cards were still broken. Since you're an astute reader you know what came next: the banned and restricted lists. The idea that there were some cards that would never be legal for use was appalling to large chunks of the player and collector base. Players who paid good money to get four copies (that were purchased at a premium from the collectors and hoarders who made a killing) were effectively out the differential of three copies and, since it was not in as much demand anymore, they could not flip the card to someone else to net zero on the card; the prices had already fallen. This change, though controversial, was arguably one of the best changes to deck design for Magic: having one copy added a flair of randomness (another one of Richard's original intentions, more on this later) and leveled the playing field significantly, which helped propel tournament Magic and the Duelists Convocation to international levels. It was under these guidelines that the first major tournament of Magic occurred. Let's look at the winning deck from the 1994 World Championship:

| "Zac Dolan's 1994 World Championship Deck"Magic OnlineOCTGN2ApprenticeBuy These Cards | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Creatures: 1 Clone 2 Old Man of the Sea 1 Time Elemental 1 Vesuvan Doppelganger 1 Birds of Paradise 1 Ley Druid 4 Serra Angel Artifacts: 1 Black Vise 1 Howling Mine 1 Icy Manipulator 1 Ivory Tower 2 Meekstone 1 Winter Orb Spells: 1 Ancestral Recall 1 Control Magic 1 Mana Drain 1 Recall 1 Siren's Call 2 Stasis 1 Timetwister 1 Time Walk 1 Regrowth 1 Armageddon 2 Disenchant 1 Kismet 4 Swords to Plowshares 1 Wrath of God | Mana Sources: 1 Library of Alexandria 4 Savannah 2 Strip Mine 4 Tropical Island 4 Tundra 1 Black Lotus 1 Mox Emerald 1 Mox Ruby 1 Mox Pearl 1 Mox Sapphire 1 Mox Jet 1 Sol Ring 1 Mana Vault | Sideboard: 1 Chaos Orb 1 Circle of Protection: Red 1 Copy Artifact 1 Diamond Valley 1 In the Eye of Chaos 1 Floral Spuzzem 2 Karma 1 Magical Hack 1 Powersink 1 Presence of the Master 1 Reverse Damage 1 Sleight of Mind 1 Kismet 1 Winter Blast |

Notice anything unusual to you? The biggest sight will be the numerous singleton copies: many of these cards were on the restricted list at the time (like Chaos Orb which was actually tournament legal at the time!). Other cards that weren't on the restricted list still were included with only one or two copies. These decks were, at the time, the forefront of cutting edge tech in Magic. They packed as much power as possible into the colors they played. There were tenacious, nail-biting decks where top decks could mean a huge swing in the game state.

Then, the final major revolution in deck design occurred: the advent of Sligh. Shortly before the darkest hour of Magic, the Combo Winter, Necropotence decks were all the rage. The card advantage power of the Necro engine has only been rivaled a few times (see Yawgmoth's Will) since. Nothing could consistently beat the Necro decks until eyebrows across the newly populated Magic UseNet groups were raised when they saw this deck list from one of the first documented PTQs:

| "Sligh: The Geeba Deck"Magic OnlineOCTGN2ApprenticeBuy These Cards | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Creatures: 2 Dragon Whelp 2 Brothers of Fire 2 Orcish Artillery 2 Orcish Cannoneers 4 Ironclaw Orcs 3 Dwarven Lieutenant 2 Orcish Librarian 4 Brass Man 2 Dwarven Trader 2 Goblin of the Flarg | Spells: 1 Black Vise 1 Shatter 1 Detonate 4 Lightning Bolt 4 Incinerate 1 Fireball 1 Immolation Lands: 4 Strip Mine 4 Mishra's Factory 2 Dwarven Ruins 13 Mountain | Sideboard: 1 Shatter 1 Detonate 1 Fireball 1 Meekstone 1 Zuran Orb 3 Active Volcano 2 Serrated Arrows 1 An-Zerrin Ruins 4 Manabarbs |

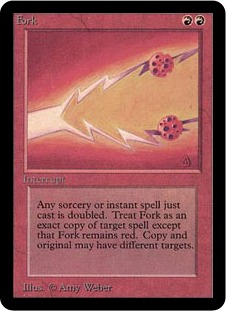

Still underrated today.

Jay Schneider was a visionary designer. This was his brainchild but, due to non-Magic life, he could not play with it in the Atlanta PTQ so instead his buddy Paul Sligh did. Funny how things work out like that. His concept of following a mana curve to continue to apply pressure to the opponent by maximizing use of the available resources every turn wasn't just a "different" idea; the novel concept brought clarity and restructuring to the design of decks the world over. If you look at your average Vintage deck today you still see many singletons at work: broken cards are broken. If you look at Legacy legal decks, four-ofs are the norm far and away. The idea of consistency in design is the reigning champ in a world where broken cards are removed.

A degree in mathematics wouldn't hurt.

The statistics of card drawing have yielded a modern era filled with probabilities driven by hyper geometric combinatorial problems for predicting the availability of cards through drawing from a randomized deck. Software and code has been written numerous times over to assist players in deck analysis to perfect the level of consistency which, the prevailing theory and results indicate, generate optimal win capability. And in the traditional precedence set by Showtime's program Penn and Teller's ********, that idea, optimal win capability via statistically tuned card drawing, is humbug.

From a numerical perspective (which can be used to show almost anything you want; see the fourth season of the aforementioned show), all you have shown is what the odds are that you should draw a card given the assumed conditions under examination. Ultimately, however, the capability of a deck to draw what is needed to win right now is still random and how you interpret that is always an underlying assumption of the game state. However, as competitive players will attest to, the capability of a deck to win is not predicated entirely upon how often you should be drawing what cards, but instead on what decks you are matched up to play against. The metagame has a much more dominating influence on what decks you could be matched up with and, therefore, should bring to compete with. This dynamic predicates the cards you will be using much more than any analysis on how you look at the odds of drawing the cards in your deck. To put it into other words, when you get ready to compete and you have tuned a deck to the point of consistent drawing you are not longer concerned with calculating how often you will have drawn Cryptic Command assuming specific game situations but instead be looking fully understand if Faeries is still the dominating deck with the best overall match-ups across the expected selection of available decks at the tournament you're going to and, more importantly, if Faeries isn't the best deck of choice then what should the next logical choice of deck be? Whether you're bringing a deck that foils the expected metagame or a deck that plays into the metagame with tweaks to beat the mirror match is irrelevant when you are considering overall win potential: the deck that will win overall may be terrible in the match up, for example.

Sounds pretty thick, right? Not really. Let's look at lands. When you create a new deck one of the last steps many of us take is to fill out the mana base. After all, we don't know what lands we'll need until we have the deck, right? How many times after you've "finished" the deck and added your lands do you shuffle it up and goldfish to see how the deck is flowing? Five times? Six times? Of course, the more practical question at this point is "How many times would I need to shuffle up my deck to see if the lands are right?"

The answer: it is entirely impossible to predict for everyone. Here's why: what the "right" number of lands for your deck is a factor of both the number of lands you include (the hedging the statistical odds of drawing lands) and your play style and comfort level of having those lands. What I mean to say is that just by having the right mix and types of lands in your deck does not guarantee color fixing or having the right combination in your opening hands. Even if you focus on this you will find, and quickly, that you must make a clear choice: hedging the odds in favor of having the right mix of lands (by including more) or hedging the power level of the deck by accepting greater risk in not having the lands but including more power (tighter mana base).

Ultimately, I want to convey to you that statistical odds and the probability of card drawing can be an important and powerful tool in how you get through tuning a deck, but it isn't the most important consideration in building your deck. Don't believe me? Like Penn and Teller, let's look at some evidence and apply logical reasoning.

Case 1: Mathematical Perfection

The following is purely speculative number crafting to put something comprehensible down. I heartily welcome further discussion on mathematically defining the equation that solves the following question: How many 60-card main, 15-card sideboard decks are there in Magic? Once defined, solving it is likely trivial; it is entirely how it is defined that determines the solution.

Number of Creature cards: 942

Number of Artifact cards: 104 (colorless) 56 (colored)

Number of Enchantment cards: 153

Number of Sorcery cards: 176

Number of Instant cards: 189

Number of Planeswalker cards: 10

Number of Nonbasic Land cards: 69

Number of Basic Land cards: 5

Total Number of Unique Cards in Standard: 1630

How many decks are there available total?

Done calculating? Before I give you my answer, let's review a few basic rules of deck building: you may have no more than four copies of any nonbasic card in your deck; you may have any number of basic lands in your deck; you must have at least 60 cards in your deck. Here's my answer: way too many to give legitimate thought to. Confused? You should be; we haven't talked about what it means to have a Magic deck. You must have cards that allow you to win; decks filled with lands and cards that don't move you towards a victory condition (like dealing damage or removing cards from your opponent's library) aren't really decks for playing Magic. You must have a deck of a manageable size; except for very special circumstances, decks with 80, 150, or more cards total will be more difficult to pilot to victory than decks that stay as close to the minimum as possible (it increases the consistency of your deck by having less stuff you don't want in it). You must actually own the copies of the cards you would like to use; a deck where you need four copies of Nicol Bolas, Planeswalker, Sarkhan Vol, and Progenitus will likely be difficult to assemble and unwieldy to use (there are more efficient and cost-effective routes to victory than powerful mythic rares).

Constructing a new deck for Standard also requires knowledge of the current balance of decks in the metagame (what current decks are performing better than other decks or, more easily put, what decks you need to beat to be successful). It requires intimate knowledge of these decks and what makes them tick, broad knowledge of other cards and how to handle the surprise cards that pop up in rogue decks, and very good rules understanding in order to properly

Is there an easier way? Absolutely. Just

I'm sure that statement just made

The ultimate idea I'm driving at is that we don't want to devote the amount of time it would take to flush these ideas out ourselves (and if you're like me and you're a slow learner it may take a very long time indeed!) so we take

This is how my head felt at this point.

The honest, dirty, ugly truth.

Mimicry-based deck design may not be the best manner by which one should go through to create a deck. There, I said it. Now, I have some serious, significant explaining to do.

Let's look at an Elves! deck list from Luis Scott-Vargas.

| "Luis Scott-Vargas's Elves!"Magic OnlineOCTGN2ApprenticeBuy These Cards | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Creatures: 4 Birchlore Rangers 4 Elves of Deep Shadow 4 Elvish Visionary 1 Eternal Witness 4 Heritage Druid 4 Llanowar Elves 4 Nettle Sentinel 1 Regal Force 2 Viridian Shaman 4 Wirewood Symbiote | Spells: 4 Glimpse of Nature 1 Grapeshot 4 Summoner's Pact 3 Weird Harvest Lands: 4 Gilt-Leaf Palace 2 Overgrown Tomb 1 Pendelhaven 9 Snow-Covered Forest | Sideboard: 1 Mycoloth 1 Nullmage Shepherd 1 Pendelhaven 2 Thorn of Amethyst 4 Thoughtseize 4 Umezawa's Jitte 2 Viridian Shaman |

Would you agree that this is a very recent example of the "genius savant" type of deck-building? Not too long ago (about a year and a half to be more precise) I sold the rare Glimpse of Nature at US$0.10 in a bulk deal. Right now it's worth more than one of my copies of Wrath of God. The power of a great mind at work is an amazing product to witness; Elves! is a very efficient combo deck that used a common creature base (Elf cards) to surprise opponents unaware of how fast it can be (turn two and three kills are nothing to sniff at, ever). The fact that the combination is both explosive and easy to produce allows even the densest players to understand how to make it "go off" for the win. Since it utilized a formerly "jank" rare and commons from the latest set it was easy to slide into the tour under the radar of the Extended players who missed the new interaction during play testing and experimentation. The originating combo came from a source online (surprise, surprise!) but the deck it appeared in was "casual" and therefore easy to miss. But coming in under the radar it avoided having to face significant, or really any, hate or effective disruption. The deck pounced into its own perfect storm for victory.

If this is what you think, I believe you're very wrong.

Elves! is a hybrid deck along the lines of a synthesis between TEPS and the old Life decks. By using efficient, cheap spells that reward you with a nearly, or greater than, one-to-one cost-benefit chain (in this case, when you combo out almost every spell is causing you to draw at least one card and provide access to more mana, gaining net resource and card advantage) which allows a storm count to get very big very quick (like TEPS). By using a creature-based combo that does not rely on giving haste to any creature you maintain explosive speed even with the fragile permanents that creatures are (similar to Life). While Life can get arbitrarily big, and Elves! can as well, the Elves! combo can cause one to draw out the entire deck and then some: instant loss unless you are knowledgeable and practiced in handling its raw power (which benefits professional and dedicated players more than outright "netdecking cheats"). The best part of the deck is, perhaps, that when you're dealing damage there is often little difference between "arbitrarily large" and "something above at least 20": either way you win and you win quickly even if you hit a speedbump.

Now known for combo potential.

Of course, this shout out to Johnnies fell deaf to many of our ears. This is why we don't get to play at Worlds. (But don't worry Spike: you can still talk on the internet like you do play at Worlds when evaluating some Timmy's deck. I only added this line to get all three Magic psychographics into one paragraph.)

And now, something completely different.

So we can't just "test everything from everywhere" and we aren't LSV and company (unless you are, in which case please send an email; the awesome humility of a great player reading my work would be a phenomenal achievement for me!): where do we go and what do we do now?

The following idea is not established, rooted Magic theory, at least in a practical sense; it is the culmination of my years of playing with random cards, building decks from whatever jank I could find in a nickel bin, and actively reading every bit of Magic theory and deck building information I could get my hands on. My current life's work in Magic can be summed up with this paradigm:

How to Build a Winning Fun Deck:

I. Define my terms forwinning having fun.

II. Choose my color(s) to include the most efficient cards to achieve that definition.

III. Build a mana-tight, 60-card deck.

IV. Test thoroughly most of the cards I've considered by:

a. Trying the cards I thought were good.

b. Trying the cards I thought were bad.

c. Keeping the cards that give me the most flexibility against multiple other decks.

V. Create a sideboard to match my needs (tournament, casual, or multiplayer transformation).

I. Define my terms for

II. Choose my color(s) to include the most efficient cards to achieve that definition.

III. Build a mana-tight, 60-card deck.

IV. Test thoroughly most of the cards I've considered by:

a. Trying the cards I thought were good.

b. Trying the cards I thought were bad.

c. Keeping the cards that give me the most flexibility against multiple other decks.

V. Create a sideboard to match my needs (tournament, casual, or multiplayer transformation).

It doesn't look like much, does it? Certainly not ground breaking or too advanced for most of us to understand, right?

This should be oddly comforting and familiar for many of you. Here's the real kicker, and it goes back to a problem illustrated above: how you define the first item is the most difficult decision by far. Many tournament players focus on one goal: getting the opponent's life total to 0 as fast as possible. This is a very effective definition for winning (Zoo, TEPS, Sligh). A few players take a defensive approach and play to stop you from taking their life total to 0 first (Deathcloud, Rock, Life, Stasis.dec). This is sometimes just as effective and can generate great dynamic matchups.

You need this in real life to win.

Obviously, any random definition of winning creates a biased game usually in the favor of "deal 20 damage faster than you" and not any other way around. Elves! win conditions happened to also meet the same criterion of "deal 20 damage really quickly" as a result of the underlying environment: building a competitive deck for Extended where you have to be playing to win quickly or to stop your opponent from winning at all. You must be able to beat decks that say "you don't get to point spells at me" and "you don't get creatures to attack me with." Elves! did both and was tuned just for these purposes, and the deck would look very different if it had to be designed for multiplayer or Legacy. Layering definitions is like putting constraints on your cards (more on this below): "winning tournaments with this deck" is a very tough constraint to manage.

Perfection is an unattainable goal.

The reason I love Elves! isn't necessarily because I'm a a closet Johnny (ask my friends; they'll tell you straight out I enjoy a good combo) but that it fell neatly into my personal theory of deck design: it is a boon of vindication for me to say "You know, I just may be onto something here." Am I the best deck designer out there and do the pros consult me on their designs? No, not for as much as I am unknown but because I don't have experience tackling the "winning tournaments with this deck" constraint in a successful manner. I like what I do (random, casual, and theme decks) and I find it both pleasant and successful enough in action, and I've taught others my approach to great effect.

It is really easy to find a "good" deck list. With some practice and reading many players become fairly proficient at using said deck list. For some, this once alien and new deck becomes an extension of their Magic capability and they wield it with fearsome knowledge and skill. A select rare few go on to modify and actually improve the deck through their playing. But I argue that many of us don't have either the raw natural talent or well-oiled play testing machine/group to run these "netdecks" through: we work best with what we, clumsily as we have done, carved with our own hands and Frankenstein-ed together with the cards we actually own. Moving through an effective paradigm, that we ourselves experience and relate to, allows us to build a better deck that we know the in and out of.

I. Define my terms for winning having fun.

Take your aim at what your heart desires. Whether it is a blistering fast deck that will take life down to 0 at any cost, a fanatical tempo deck with many versatile and effective spells and creatures, or even a lock down deck that allows your opponent no chance to escape, you must have your own definition. However, be forewarned, most definitions will not result in a consistent, effective capability to win. Just because you want a lock down deck doesn't mean you opponent won't have the means, be it speed or power, to beat you to the punch. A tempo deck may run into a combo deck that is too explosive to stop. A blistering fast deck may run into a deck with defensive capabilities too great to overpower in the first few turns, leaving you out of gas and options by the mid-game. The many allegories to Rock-Paper-Scissors isn't meant to justify a narrow metagame but instead to illuminate that every deck has a foil and therefore can be foiled. Even if the foil is a very narrow, targeting deck (see the Skullclamp era) it will be run if the biggest deck is the one it's meant to kill.

Always one-way fun with this out.

Consider this: if you take "a deck that is fairly inexpensive to put together," "a deck that wins very quickly," and "a deck that has the most consistent manabase" as a structural definition, you make decks like ElfBall, Burn, and Suicide Black. These decks attempt to blaze into battle, guns drawn and firing, throwing everything they have generally as fast as they possibly can. If they succeed, so what? They got the job done. If they fail, you are probably left with little in resources and facing insurmountable card advantage since you ran into a deck designed to foil such "fight or fail" strategies. For some, this is an exciting (or only affordable) way to play competitively. For others it will be frustratingly inconsistent and underwhelming to consider bringing to a tournament due to the perceived lack of control and sustainability of the deck.

There is no right answer for everyone, only you. Your buddy can talk about "winning fast" or "playing casual" until he or she is blue in the face; you define your fun (a justification for the fact that I state that the "Dave" type both exists and actively seeks to wreak havoc on your world). However, just because something is "fun" for you doesn't give you the right to inflict it upon everyone else: "too casual" and "too competitive" is a vague spectrum best covered elsewhere.

II. Choose my color(s) to include the most efficient cards to achieve that definition.

Your experience, and that of others as well, plays a heavy role in what you put into your decks. Tournament decks, theme decks, intro decks, sealed and draft decks, netdecks, variant format decks, and multiplayer decks all flavor your knowledge base with information. This information can be conflicting: "efficient or effective" in sealed is often very different from constructed. Multiplayer decks will often look very different from non-multiplayer decks. Colors and splashes will vary within archetypes and metagames. The reasoning, logic, and play results vary by the skill levels and nature of the games played.

Becomes one with the Shyft.

These sort of decisions are a reflection of relevant experience with Magic and the distilled wisdom from that experience. But don't fear if you don't have the wisdom yet yourself: become the student and begin to dig into your goal through research. Articles, like perhaps one day this one itself, and discussion on the internet often contains significant amounts of wisdom for you to take for yourself. Talk to your friends on these internet discussions and at your local gaming spot; they will often gladly share their thoughts and experiences. Turn to aggregating databases, like Wizards' own Gatherer, to look up cards with terms you are interested in. Some of these databases allow you to buy cards right from your search, making it very convenient to order exactly what you need (or accidentally order what you don't; always check your order before placing it!).

III. Build a mana-tight, 60-card deck.

Unless you're building for a special variant format (EDH, Rainbow Stairwell, Pauper/Peasant), 60-card decks are an effective base to work with. By using the de facto maximum number of cards for a Magic deck you are simplifying a potentially very large variable. While having 70 cards in a deck is probably fine (and I've made quite a few of these "loose" decks), it will restrict your ability to craft an efficient mana base.

You don't belong here, do you?

With an effective mana base in a 60-card deck, you should be capable of a normalized mana curve. Should every deck have a play every turn for the first five turns? No, but having the capability to function on the turns you need to is still having a mana curve. When I create a multiplayer deck, turns three and four are where the fullest extent of my curves live: I want the power that area of the curve provides and with multiple players I will almost always get the time to make it there. If it's a tournament deck I will generally lean towards having turn two plays primarily drive my cards. Quite often, how I'd like to be playing rides more on the cards I put into my deck than the strategy I set out to follow. Regardless of what I'm drawing I need the ability to use it: my lands define my decks.

IV. Test thoroughly most of the cards I've considered:

a. Trying the cards I thought were good.

b. Trying the cards I thought were bad.

c. Keeping the cards that give me the most flexibility against multiple other decks.

a. Trying the cards I thought were good.

b. Trying the cards I thought were bad.

c. Keeping the cards that give me the most flexibility against multiple other decks.

Playing your deck is the only way to see what it does. No amount of thought, statistical work, and theory-crafting of your deck can equate what playing it a few dozens times will tell you. Many decks look and feel good on paper but fail to realize the potential they should have. Consider a classic "good stuff" deck that uses many very effective cards. Effective individual cards do not always yield a synergy of layered plays that propel a deck effectively to winning. A card that is both efficient and effective for a desired goal may not be the right choice over another card that gives you more choices in how you can act in a broader spectrum. Decks do not live in a vacuum and they cannot be played that way (even decks that otherwise ignore an opponent). Even classic Draw-Go decks relied on an assumed strategy from opponents and could falter against the few decks that didn't fall into the types it anticipated.

Anyone who has been to a major tournament has seen the inevitable game: a great player with a sub-par deck playing against a rookie/weak player with a "better" deck. The great player will generally find and create avenues to victory and win. Great players see great plays and create them. A deck does not necessarily define for you what you can and can't do: you can push the deck to do what you need be doing. A classic illustration is the "tunnel vision" that we all get: you see a creature/enchantment/artifact/planeswalker and think "I have to get rid of this." and instead of seeing a path to winning, you becomes blind and flail at a distraction; you defeat yourself by focusing on the distraction instead of moving ahead to capitalize on the fact your opponent can still lose. What you try to do with your deck is your goal and, generally speaking, if your goal is to win you should play to win. When building a path, it may be more direct to take it right through the mountain that sits in our way but to get there faster you sometimes just take the dirty, rough road around it.

This is going too far.

Ultimately, you may revisit every step in deck design before this and find that your goal may be unattainable, your colors may be untenable, your land may be completely wrong or changes as a result of card decisions, and as new sets are released even your most venerable of decks may adapt and change to new cards and potentials. One concept, however, will become clear: your deck will either become specialized within a specific environment (tournament play, multiplayer play, one-trick-pony, low-balled for learners and those new to Magic, etc.) or become broader and more flexible, capable of performing different duties and adapting to various game states. This allows you to finalize your deck with a sideboard.

V. Create a sideboard to match my needs (tournament, casual, or multiplayer transformation).

Finally, the cards that were just barely cut, provide access to highly specialized protection or abilities, or allow you to take on multiple opponents can be assembled into a sideboard. Sideboards are the most challenging aspect of building you deck after trying to define it initially. You must determine what you will use your deck for and what you deck may most need dependent upon other circumstances. This is all practical guesswork combined with a touch of pessimism. "What will break my deck?" "How to beat two/three/more people?" "What if I want to switch to a more control-based deck instead of aggro?" "What if somebody brings Deck Q to the tournament?" There are dozens of questions to potentially answer with each question pulling your deck in a different direction: you can't answer them all and you will close doors in accepting some as more important to fulfill.

This is as flexible as it gets.

Everything I know is wrong.

More is always better, right?

Recall from above how I look at the lands you can use defining the deck and driving what I can do and not the other way around? My approach inherently runs counter to the most powerful piece of Magic deck theory from the last 15 years: more copies of cards will, inherently, cause an incremental gain in occurrences of drawing that card and, over playing enough games, will inevitably result in the benefit of having the occurrence of using that card happen more frequently. Lands are just the resource you base around that.

And so I am left faced with an impossible decision: accept my fate and run the 60-card max/four-copies model, or playing hard ball, trying 61/4, 60/3, and other deck numbers? If I play hard can I find a away to show my idea that flexibility and capability will edge out over the predominance of statistical percentages and hedging the odds? Is there a way to empirically gather data, without generating an intentional bias, that will confirm or deny my hypothesis?

Hypothesis: A 61/3 deck will not perform as well as a 60/4 deck.

By defining a null hypothesis I hope to see the data confirm or deny the hypothesis. What types of data would I need?

1. Minimize the deck variables via specific deck lists matched against other specific decks over several months.

2. Attain at least a tenable t number by obtaining testing buy-in without disclosing the purpose of information gathering; 30-40 participants would likely suffice.

3. Define the means of play: each deck tested must play in an optimal manner so that the deck that is inherently better will win more often.

It would be very difficult to get type (2) data: there just isn't enough people who I would recruit for my shenanigans. Further, volunteers that know the hypothesis may, intentionally or inadvertently, influence the data (or even fabricate it entirely). Data of type (3) is, actually, a hypothesis itself: an optimally played deck is impacted by player skill, opposing deck, opposing deck player's skill, and circumstance of playing (tournament, casual, multiplayer). This is a bad definition for a "data type."

This leaves me with one type of reliable data: minimizing the deck variables and playing against decks designed for the same purpose. I can build my own decks. I can play my own decks. And, more importantly, I can play against a fairly consistent field: Standard decks for Friday Night Magic.

I can ignore my ego for now.

Am I a biased subject? Indeed; but I'm also a highly pessimistic. So while my entire devotion to trying a different deck build will drive my testing and goals, my hypothesis and personal suspicion that I am wrong plays counterbalance to that. I am fresh to the current Standard environment. I just got a DCI number at the Conflux Prerelease events. I am not running with a long history of tournament experience or competitive deck building. Starting from scratch, developing a deck similar to but not the same as a popular deck and playing that deck by myself is the purest form of information gathering I can imagine right now.

Of course, I'll take in all sorts of suggestions and ideas. Many of you will be critical and judgmental about my approach. Some of you will openly condemn me and attack my very ideas. All of these comments will be used to build a better test, better deck, and hone my focus on pure results.

So join in my fun: comment in the forum, send a PM, or just dial me up personally if you know me. But please don't be angry if I don't respond right away: I have a lot of deck building and testing to try.

Comments